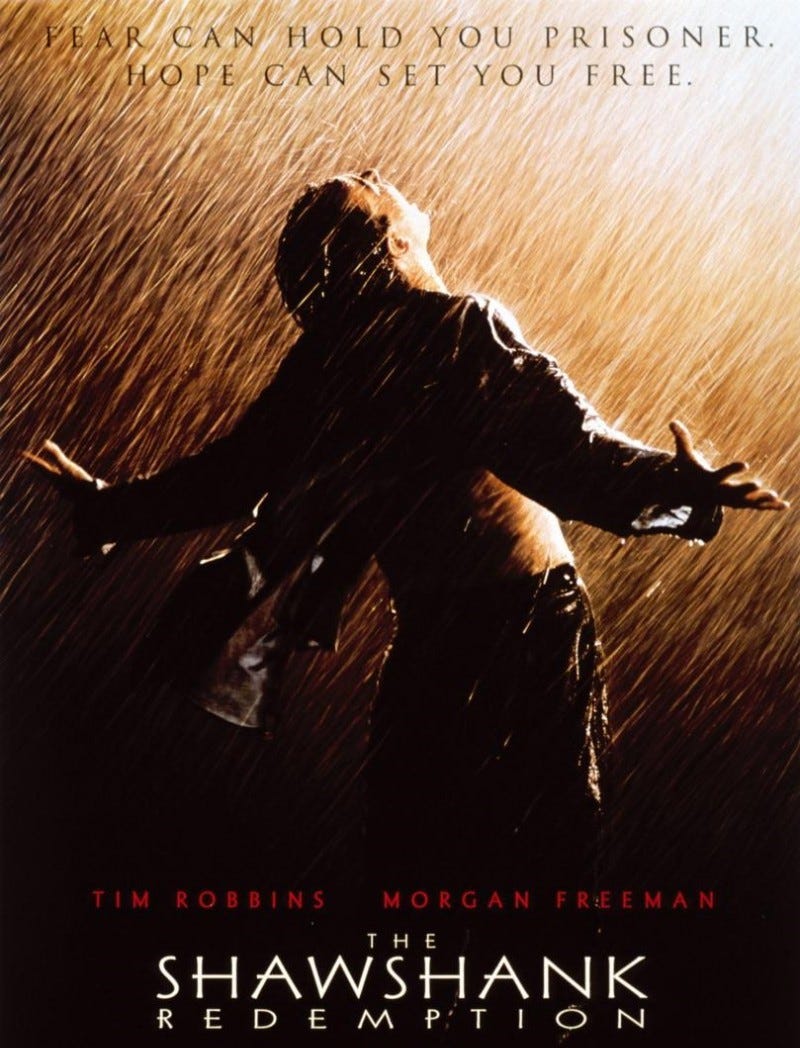

In one of my favorite movies, The Shawshank Redemption, an innocent man who is wrongfully convicted of murder and imprisoned for many years is ultimately vindicated after patiently and methodically pursuing justice. I can’t help but see similarities between this film and what happened to me as an employee of the Dudley-Tucker Library in Raymond, New Hampshire over the past year and a half. While the activity that I was persecuted for was much different and the length of time it has taken for me to be vindicated has been much shorter (although it has seemed like an eternity), both stories offer the redeeming message that justice will ultimately prevail and that, as Shakespeare wrote, “the truth will out.”

Well over a year ago, on April 5, 2023, I was fired from my job as the Assistant Director of the Dudley-Tucker Library in Raymond where I had only been working since the previous December. Like all new employees, I was still within my probationary six-month period. As far as I knew, I was performing all of my job duties in a satisfactory manner. On this particular morning, however, the library director, Kirsten Rundquist Corbett, informed me that she and the library trustees, Jill Galus, Sabrina Maltby, and Valerie Moore, had decided to fire me. I was presented with a termination letter signed by Corbett, Galus, Maltby, Moore and then-town manager Ernest Creveling. This letter claimed that I had “not fulfilled the conditions of employment because of [my] lack of separation of personal/political values and agendas from DTL policies, procedures, and occurrences.” In a sudden state of shock and confusion, I could hardly process the words contained in this document.

Unable to identify any negative actions on the job that could have justified my dismissal, I asked if my termination had anything to do with my recent political activity in my hometown of Atkinson, New Hampshire, which I represent in the State Legislature. A couple of months earlier, I had recruited two conservative candidates to run for the board of library trustees in Atkinson, and I had continued to support them in their campaigns. This activity included writing an endorsement letter to a local newspaper that highlighted how these candidates believed in “protecting our children from the increasing amount of inappropriate material available both in print and online without sacrificing the intellectual freedom that has always characterized public libraries.” To my disbelief, Corbett affirmed my suspicions. Understandably upset, I succumbed to the natural “fight or flight” response by opting for the latter choice; I wanted to get out of that library immediately. Completely blindsided, I signed the termination letter and left. Only later would feelings of indignation motivate me to fight back.

Suddenly finding myself without a job, I reflected back on the weeks preceding my termination. I recalled the very politically charged environment I surprisingly found myself in. Some concerned Raymond residents had drafted warrant articles pertaining to the library that were to be voted on during that town’s upcoming election in March. One of these articles called for the removal from the children’s room of inappropriate material while the other pertained to the Dudley-Tucker Library ending its membership with the American Library Association, an organization which has been increasingly called out for promoting inappropriate material to children. In the weeks leading up to this election, many patrons commented to staff about these warrant articles when they came into the library both in support and in opposition. I tried to maintain an appropriately neutral position throughout this time even though other staff members freely expressed their opinions. The trustees even made a video that was posted on the library’s Facebook page by the director advising citizens to vote against the warrant articles, a situation that eventually led to the New Hampshire Attorney General sending a “cease and desist” letter to the director and trustees in response to this clear violation of electioneering laws.

In the days that followed my termination, I thought about this double standard, and I began to realize that a great wrong had been done to me. The trustees and director had egregiously violated my First Amendment right to free speech by terminating me for recruiting, supporting, and endorsing conservative library trustee candidates. I was fired for voicing my opinion about candidates outside of work time and even outside of the town I worked in. I began to wonder if I would have been fired if I had supported candidates who espoused beliefs more congruent with the ALA agenda.

I realized that, while new employees on probation can be fired for just about any reason, they cannot be fired for a reason protected by the Constitution. My right to support any candidate is ensured by the First Amendment. As permitted by state law (NH RSA 202-A:17), I requested a public hearing to discuss the circumstances related to my termination. While waiting for a response to this request, I also obtained a copy of my personnel file. This file included a copy of my published letter-to-the-editor mentioned above. The phrase “protecting our children from the increasing amount of inappropriate material available both in print and online” was highlighted, apparently because it was a section that was considered controversial. My endorsement obviously implied that I held the same belief, and this was the belief that the trustees and director objected to me speaking out against. To my utter astonishment, I also found a copy of a private e-mail message in my employee file. This message had been sent to the chair of my local Republican club and was only intended to be distributed to members of that group with the purpose of recruiting conservative library trustee candidates.

When I did not receive a response to my request for a public hearing after a week, I sent another request, this time threatening legal action. Two days later, on Friday, April 21st, I was surprised to receive a termination rescindment letter. Obviously, my adversaries had realized that they had done something wrong and didn’t want to get in trouble, so they attempted to brush their error under the rug. Returning to work three weeks after my dismissal, I felt like I had entered some sort of “twilight zone” in which I had never left, had never been fired, and had never been gone. There was no recognition that something egregious had happened, no apology, and no mention of my termination.

Despite being rehired and even being paid for the time I had been away, this ignoring of a great wrongdoing was troubling to me. Where was the justice and the certitude that such a violation would not ever happen again? Although I was re-hired with back pay, I was left feeling that justice had not been adequately served. I found it particularly troubling that the library trustees had violated my rights because, like all elected officials, they take an oath of office in which they swear allegiance to the Constitution. By wrongfully terminating me, these trustees had violated their oaths by infringing on one of the most important rights in the Constitution—freedom of speech. My reinstatement alone did not achieve adequate justice because the crime that the trustees and director committed had gone unrecognized.

In search of a more satisfactory resolution to this situation, I sought a legal remedy. I spent the next few months seeking legal representation from a number of nationally recognized organizations, but these groups unfortunately declined my case because it didn’t quite fit in with their missions. My final attempt at securing justice was a plea to the American Center for Law and Justice (ACLJ). I assumed that my request for legal representation would be denied until I heard back from ACLJ attorney Nathan Moelker. Speaking with Mr. Moelker at length one afternoon last August, I felt that someone finally understood what I was fighting for – not money or revenge, but simple justice.

Over the next couple of months, I frequently communicated with Mr. Moelker and the lawsuit was officially filed on October 27, 2023. In the months that followed as Mr. Moelker and his associate Ben Sisney negotiated with the defendants’ counsel, I found it extremely awkward and difficult to go into work every day having to interact with a supervisor who I was suing as well as the other defendants who frequently came into the library.

While this lawsuit initially demanded a jury trial, I was concerned about the amount of time such a trial would take and the emotional distress that it would cause. During negotiations between the lawyers on both sides, a financial offer was made in exchange for my resignation. Such a settlement, however, did not feel right to me because it would give the defendants exactly what they had wanted when they committed their original crime – my departure. I ultimately rejected this offer and remained at my job, difficult as it was to do so. Since my goal was to simply secure some recognition of wrongdoing and the assurance that such wrongdoing would never happen again, I ultimately agreed to a settlement that would achieve these ends in the form of a “consent decree.”

Finally, the defendants agreed to this decree. Basically, this document acknowledges that the “Dudley Tucker Library regrets its conduct toward [me] and the violation of [my] constitutional rights.” The decree loudly and clearly declares that terminating me for my political activity “constituted a violation of [my] First Amendment rights”! It further assures that the library and the town “will take any other actions reasonably necessary to ensure this type of constitutional violation does not occur again.” The decree recognizes the right of town employees to engage in political activities when not at work. It even stipulates that the town employee handbook must be revised to include a section acknowledging the right of employees to participate in political activism outside of work.

I have since left my job as Assistant Director of the Dudley-Tucker Library, but my resignation was offered in order that I can pursue a new opportunity, not because I would receive financial compensation in exchange for acquiescing to the demands of those who wronged me. Once an acknowledgement of their wrongdoing was finally made and a promise that such a transgression could never happen again, I left my job. This recognition is all that I had ever wanted during the many months that followed their egregious violation of the First Amendment. Such a violation seemed especially hypocritical since it happened in a public library, an institution that is supposed to be a shrine to free speech and intellectual freedom. I consider the resolution of my case, thanks to the hard work of the American Center for Law and Justice, to have ensured the redemption of one such institution, and I hope that it serves as an example to every public library not only in New Hampshire but throughout the entire country.

I would like to acknowledge the ACLJ for representing me pro-bono. Such representation is made possible through the generosity of donors who truly support justice. Please consider financially supporting the ACLJ!